Last Friday was an extraordinary day. Eclipse day. I awoke to mostly clear weather and couldn’t quite believe our luck. As I walked down through Longyearbyen towards the university (UNIS) just before seven o’clock, there was a large lenticular cloud hugging the summit of the mountain across the fjord, and some wispy, pink cirrus clouds up high. Otherwise the sky was blue. I met my friend Pål (pronounced Paul) at UNIS, an optics specialist in the atmospheric physics group, and we went across to the old aurora station in Adventdalen. Visiting scientists were there setting up their equipment for imaging and spectroscopy, and the Norwegian broadcaster NRK was preparing for a live broadcast. Pål set up his telescope and camera. The clouds disappeared and the sky became a perfect blue, the sun shining strong and clear and reflecting brightly around the snowy mountain landscape. Read more

Aurora in the Wilderness

Reindalen was vast and beautiful – a wide, long expanse edged by flattened mountains that looked like a giant line of piled white sugar subsiding into the valley. The surface was mostly icy crust, again with puddles of snow, so pulling the sleds was relatively easy but we were accompanied always by the loud scraping sound of skis over uneven, frosty ice. It was too loud to talk. We progressed in our own individual worlds. Every hour or so we would stop for a very quick break – put on a down jacket, drink some water from our flasks, sit on our sleds and eat a few nuts or a biscuit, swapping our hands in our mitts between each action to prevent the fingers becoming painful from cold. Despite my best efforts they would hurt anyway, and it was always a relief to get going again and for the pain in the fingers to gradually diminish.

Setting Out Skiing Spitsbergen

I have recently been out skiing across Svalbard. The trip was more intense – more brutal – than I could have imagined. I realised that out there everything becomes about survival and nothing else matters.

Nansen’s ship Fram

I am in Longyearbyen on Svalbard, the Norwegian archipelago at around 80 degrees North.

On my way to Svalbard I spent a day in Oslo. I visited the Fram Museum and saw the polar expedition ship that I had read so much about. It’s rests in a dry dock on the peninsula of Bygdøy, housed in a triangular-tent-shaped building where one can circle the ship whilst reading about polar expeditions past.

Anticipating Aurora & Eclipse

“You should be here earlier in the winter. When it was colder,” said Knut, the Sami reindeer herder in his gruff, accented English. “Now it’s warm weather, rain, we can’t see the northern lights.”

“We haven’t seen them at all since I’ve been here,” I replied. “That’s nearly a week. It’s been cloudy every day.”

“When it’s so warm it [the northern lights] doesn’t come.”

“When is the best time to see it?”

“December or January. When it’s very cold.”

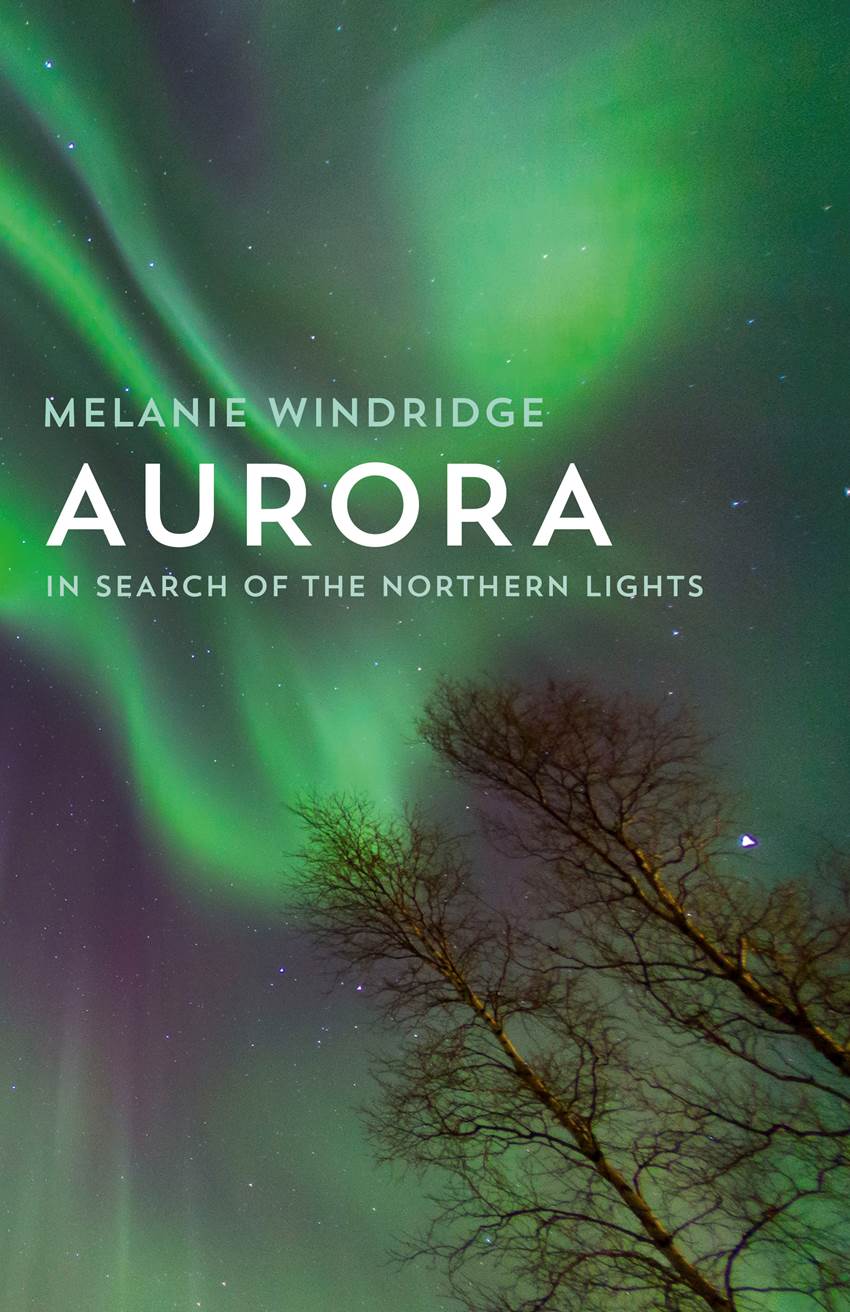

We were out in the hills with the reindeer somewhere around Karasjok, a few hours’ drive inland from Alta, near the Norwegian–Finnish border. That was March last year. I was in northern Norway researching a book I am writing on the northern lights. I am a plasma physicist and the aurora is plasma, so despite my academic interests in nuclear fusion (I was the IOP Schools’ Lecturer in 2010 on this subject), the northern lights have long fascinated me. Read more

Insulation 2 – a different lesson

Mountain Science – preliminary results 5

This post is about an experiment I did that gave quite unexpected results.

As well as looking at insulation of particular fabrics, as in the previous blog, I wanted to have a look at the insulating properties of some of my stuff – my socks and gloves. I did this using a Raspberry Pi. Anyone with a Pi can set theirs up so they can do this too. If you do, please share your results with me.

The Raspberry Pi was set up with a temperature sensor and a real-time clock. For information on how to do this see http://www.raspberrypi.org/learning/temperature-log/ When plugged in to a battery it boots up then takes temperature readings every ten seconds for 500s in total. Then it turns off.

I did the experiments when I was confined to my tent during the snow storm on the way to Putha Hiunchuli. Below is a picture of the items I tested: three pairs of Teko socks (thin, medium and thick); two pairs of Mountain Hardwear gloves (medium and thick); and a thin pair of silk liner gloves.

The experiment involved putting the warmed Raspberry Pi in a sock or glove, turning it on and putting the ensemble out in the cold while it took readings. The Pi was warmed in my sleeping bag between readings. This kept me occupied for most of the afternoon while we were snowed in.

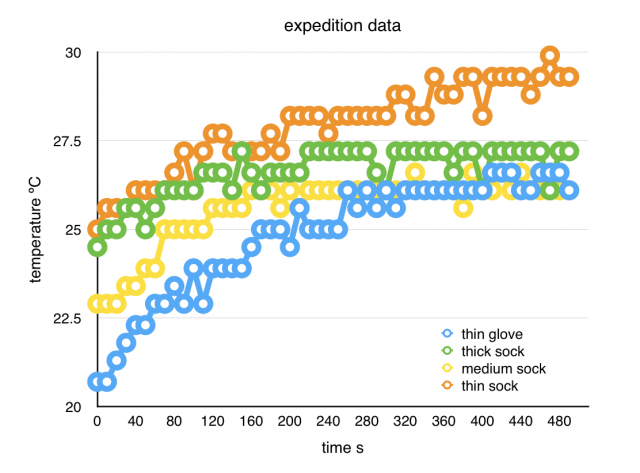

When I returned to England I downloaded the data from my Raspberry Pi. Unfortunately, not all the runs had saved properly, but what I have is plotted below. Do you notice anything odd about this graph? Would you accept these results?

Yup, it’s going the wrong way. In the tent porch, according to this data, the Raspberry Pi was warming up not cooling down. Hmmm. This is a mystery. I still don’t know why this happened. Was the Pi placed too close to the battery and the battery heating up? (See picture below of the grubby experimental conditions.) It seems unlikely, but I have no idea why the porch was warmer.

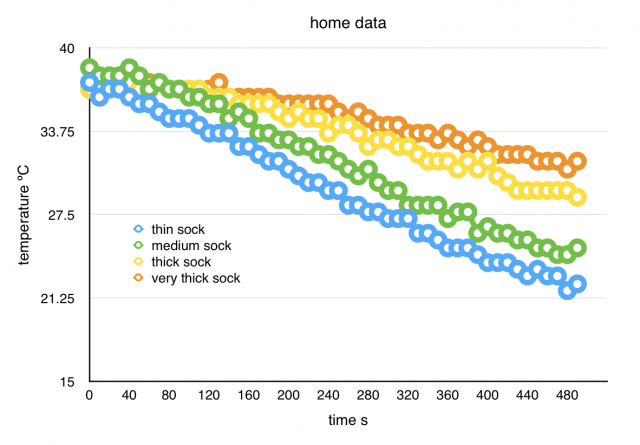

I repeated the experiment at home, this time putting the Raspberry Pi in the freezer as it took readings. At home the Pi was in the bottom drawer of the freezer and the battery hanging outside so it couldn’t affect the Pi. I did it just with socks this time, adding a very thick Teko expedition sock. The results are below.

These data look a bit more like we would expect – the Raspberry Pi is getting colder! We can also see that the thicker the sock the warmer it kept the Pi, .i.e. the better the insulation. The thicker socks trap more air, as discussed in the previous blog, so they keep our feet warmer.

This experiment is interesting because it teaches us to think about what we expect and not to accept the data blindly. Repeat the experiment if necessary. I should really do this one again somewhere else and compare my findings. If anyone else does reproduce this experiment, please share!

Thanks to Zoltán Szenczi and to my sponsors:

Insulation

Mountain science – preliminary results 4

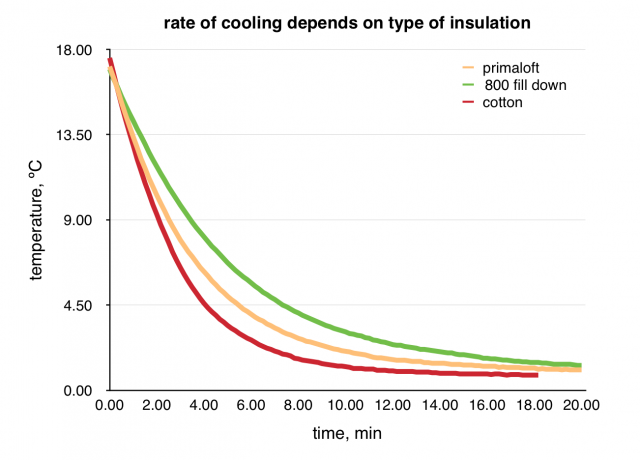

This experiment looks at the insulation properties of three different fabrics – cotton, primaloft and down.

I did a simple test with my Vernier data logger and some samples. I set the data logger up with three temperature probes and instructions to record the temperatures every 10 seconds for 20 minutes. I placed a two-layer sample of each material in its own small plastic bag (except the down, which was just a load of feathers). I then pushed one temperature probe into each bag between the layers of fabric or into the feathers so that it was completely surrounded. I pressed record on the data logger and put it all out in the snow for about 20 minutes.

Later, when I downloaded the results to my computer, this is what I found.

We can see here that the down is the most insulating material, followed by the primaloft, followed by the cotton. Someone wearing just cotton would cool off quickly in the snow, whereas wearing primaloft or, preferably, down clothing would keep them warmer for longer. This is because what actually keeps us warm is trapped air, and down traps the most air – caught between all the fluffy parts of the feathers.

One of the main ways that humans lose heat is by conduction. In the same way that a metal spoon left in a piping hot drink will soon become hot to the touch, heat is conducted through any medium by hot, rapidly-moving atoms jiggling around and hitting into colder, slower atoms and causing them to jiggle faster, so transferring the energy. Metal is a good conductor, meaning that heat energy transfers quickly through this medium. Sitting on a metal bench in the cold will cool you down faster than just sitting in the snow. Water is also a good conductor, which is why you will cool down quickly even in a warm swimming pool if you stop moving. If you fell into freezing water and couldn’t get out you would likely be dead within ten to fifteen minutes. But air is a relatively bad conductor, so trapping lots of warm air close to our skin keeps us warm. This is why layering clothes is effective, with a small amount of air trapped between each layer.

The best insulating clothing therefore traps air. Natural duck feather down is still the best material we have, despite creating fancy new materials. However down is almost useless when wet, so can only be used in dry environments. The man-made, synthetic alternative, primaloft, is not quite as insulating but it will maintain its effectiveness even when wet. So remember, your best choice of clothing depends not only on what you will be doing, but where and in what conditions you will be doing it.

Insulation samples kindly provided by Will at Rab. Cotton from the local haberdashery!

Thanks to my sponsors: