I am in Longyearbyen on Svalbard, the Norwegian archipelago at around 80 degrees North.

On my way to Svalbard I spent a day in Oslo. I visited the Fram Museum and saw the polar expedition ship that I had read so much about. It’s rests in a dry dock on the peninsula of Bygdøy, housed in a triangular-tent-shaped building where one can circle the ship whilst reading about polar expeditions past.

The Fram was built for Nansen specially for his pioneering expedition to the North Pole. His plan, which many at the time regarded as madness, was to lodge the ship in the ice purposely and drift with the current to North Pole. There was a theory that currents circulated in the Arctic Ocean, and wreckage of an American vessel caught in the ice and sunk near the Bering Strait had turned up in Greenland, convincing Nansen that it may be possible to drift to the pole. The Fram, christened by Nansen’s wife Eva and meaning “forward”, was constructed with a smooth, rounded hull so as the ice compressed it it would be pushed up rather than crushed, in the way a hazelnut squeezed low between fingers will push up and out of grip. The ship was well insulated and made homely. Leisure was considered as well as the numerous scientific measurements that must be made. There was a semi-automatic organ and other instruments, a 600-volume library and numerous games. This would be home for the next 3 years (they took food for about 6).

Walking around the Fram, I was struck by the smallness of the berths and the cabins. The ceilings are low with broad beams and the doorways are small. Men surely would have had to duck as they walked around. Not unusual for a ship perhaps, but being there and considering this was all that 13 men had for three years gave a new appreciation of the expedition. However, the ship looked comfortable (at least on dry land when it wasn’t lurching sideways) and attractive in old-style wood and burgundy velveteen. The galley looked spacious, and the men certainly didn’t want for food. Nansen in his diary frequently recounts a good meal they had. Nutrition was another aspect of the trip planned carefully. None of the men got scurvy and most gained weight.

Nansen was a scientist before an explorer and consequently all his expeditions – and others of the Fram later – had strong scientific objectives. As well as testing the theory of the east-west current and filling in blank areas on the map, the team made measurements on oceanography, meteorology, marine geology, geomagnetism, flora and fauna, and the aurora.

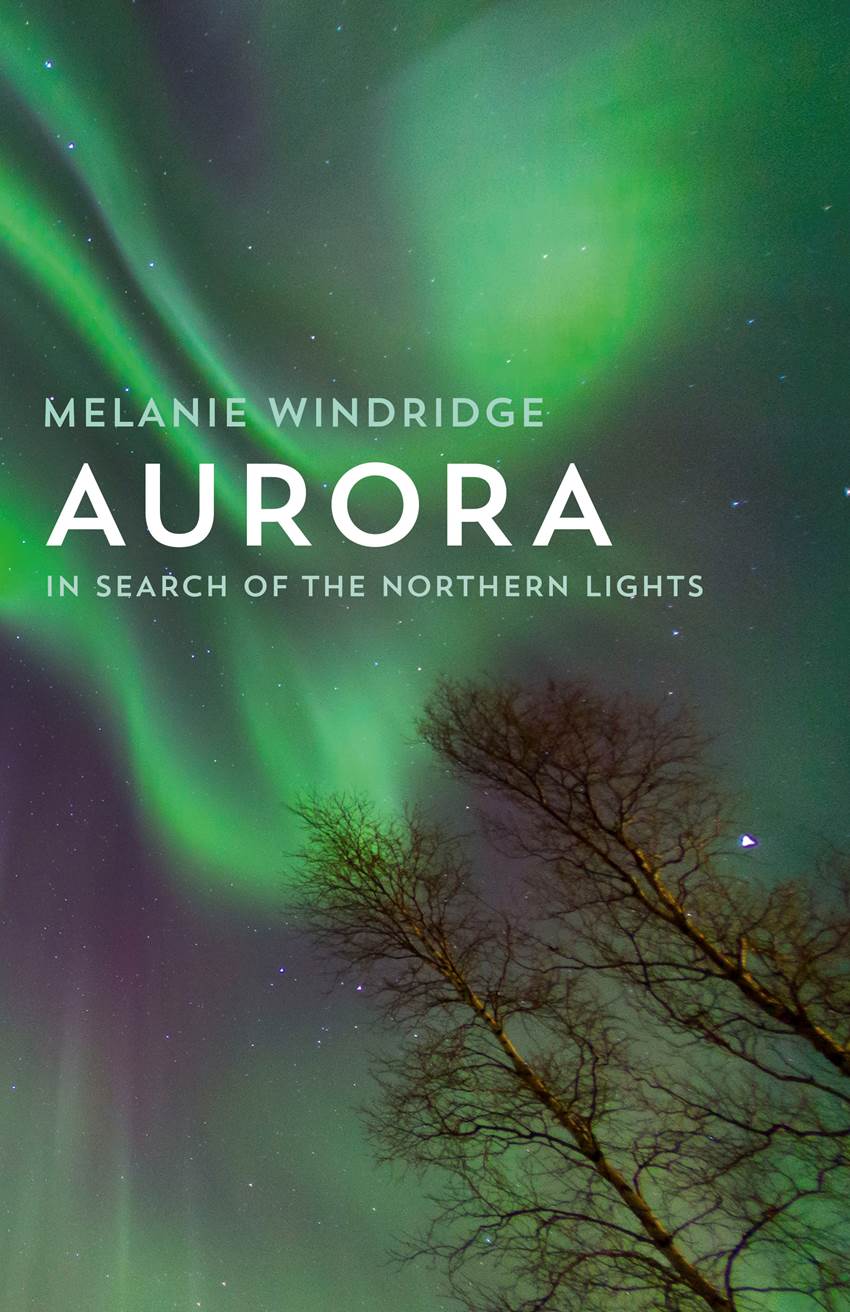

Nansen wrote in his diary that they saw northern lights almost every day when it wasn’t cloudy. He described many a good auroral display, often becoming philosophical under their light. “In the north are quivering arches of faint aurora, trembling now like awakening longings, but presently, as if at the touch of a magic wand, to storm as streams of light though the dark blue of heaven — never at peace, restless as the very soul of man.” Additionally, they witnessed a solar eclipse on 8th April 1894.

In March 1895, after two winters drifting on the Fram yet not getting closer to the pole, Nansen and one crew member, Johansen, left the ship to make a dash for the pole on skis, taking some sledges and dogs. They struggled over sea ice for about a month, reaching 86º 14’ N, further than any men had been previously, before turning round for an even longer and more perilous journey back to land. Temperatures sometimes reached almost as low as -40C. They overwintered on Franz Josef Land and were lucky to bump into Jackon’s British expedition in spring 1896. They returned with the British to Norway, arriving a week before the Fram, who had broken free of the ice.

This year, 2015, is the International Year of Light and I am a plasma physicist writing a book on the northern lights. I’ve come to Longyearbyen to visit the scientific facilities and see the solar eclipse at the end of March, but also to experience the northern lights in the remote wilderness and get a flavour of what it must have been like for Arctic explorers over a hundred years ago making forays into this inhospitable land.

My next post will be about my own ski trip across Svalbard, braving similarly low temperatures (but not contending with sea ice), to really gain an understanding of what these explorers went through.

* * *

This blog was first published on the International Year of Light UK website on 27th February 2015 as Notes from the North – Part 1. Read Part 2.

* * *

Plasma physicist and adventurer, Melanie Windridge, is on an expedition to the frozen wilderness of Svalbard to witness the northern lights. In a series of letters, she shares her experiences as she walks in the footsteps of the earliest polar explorers and battles the elements in pursuit of science. In her first post, she visits the Fram Museum – home of the historic ship Fram (“forward”) built for Fridtjof Nansen’s 1893 Arctic expedition.