Reindalen was vast and beautiful – a wide, long expanse edged by flattened mountains that looked like a giant line of piled white sugar subsiding into the valley. The surface was mostly icy crust, again with puddles of snow, so pulling the sleds was relatively easy but we were accompanied always by the loud scraping sound of skis over uneven, frosty ice. It was too loud to talk. We progressed in our own individual worlds. Every hour or so we would stop for a very quick break – put on a down jacket, drink some water from our flasks, sit on our sleds and eat a few nuts or a biscuit, swapping our hands in our mitts between each action to prevent the fingers becoming painful from cold. Despite my best efforts they would hurt anyway, and it was always a relief to get going again and for the pain in the fingers to gradually diminish.

It got colder. By day three I could no longer write my diary because my fingers were too cold even in the tent. Getting into camp was a race to get everything set up and to get warm. As the guide pitched the tent I would get the bedding, fuel, burners, pan, food and guns ready to go in. He would put up the polar bear trip wire and I would get everything inside and dig a step in the porch for easy access, piling snow up in the other half for melting for water later. Then I’d go into the tent, pump up my sleeping mat, organise, get changed and get in my sleeping bag to get warm and out the way as the guide came in. By day four when we got in the tent our clothing was stiff with frost. There was solid ice around the front collars of our jackets. I hadn’t been able to wear my goggles because the view became clouded by millions of tiny ice crystals. Taking off mittens for more than a few seconds, even in the tent, made fingers scream in pain. We lit a burner in the tent to take the edge off. It wasn’t warm, but we could function. We could pass a relatively pleasant evening once we had eaten our rehydrated food and heated up water for our bottles, chatting in our sleeping bags over the small burner. Morning was unpleasant. I never enjoyed wiping away the ice from the opening of my sleeping bag and wriggling my way out into the frigid air.

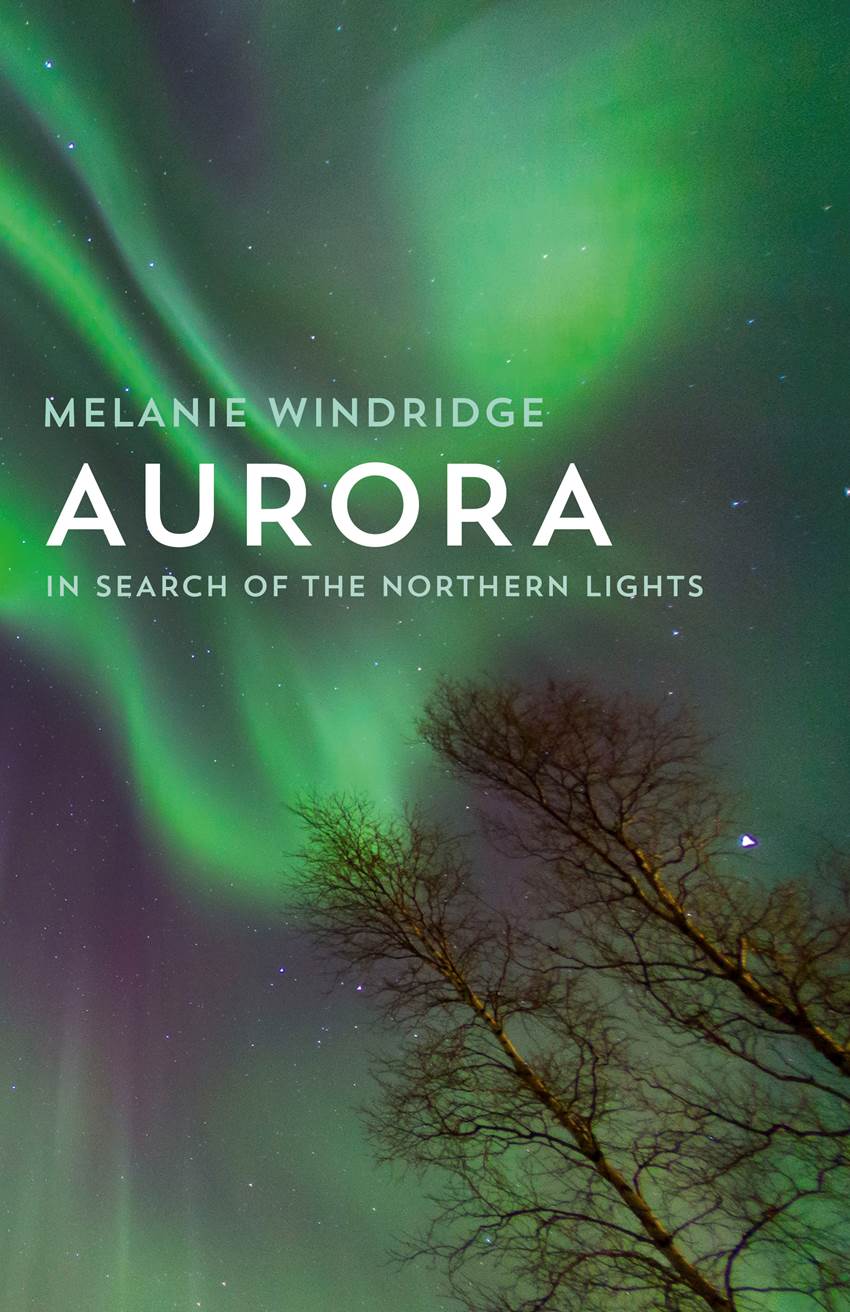

One evening I went out around eleven o’clock and saw the northern lights. They were a feint greenish white, stretched out east-west across the whole sky and reaching up in places like towers to the heavens. From where we were camped we had a wide view and it was beautiful to see the lights over the full horizon. However, what I had not been prepared for when I planned this trip was quite how cold it would be. The temperature was a huge barrier to enjoying the northern lights, not just because it was cold to stay out there watching, but because it required a huge strength of will just to leave the tent and see if there was any activity. I think I had romantic notions of enjoying the lights from a tent in the snow, but I was not prepared for what it would feel like in these temperatures. Even the guide was cold.

“This was one of the coldest trips I have ever done,” the guide said to me afterwards. “I’ve never skied in padded trousers before.” He has been guiding for ten years and has made numerous trips to the North and South Poles. He said this trip was worse than skiing to the North Pole. This is because we weren’t seeing the sun, so nothing warmed, nothing dried. Many ski trips go under the midnight sun.

I learned that the conditions the polar explorers had to endure were extreme. Out there, everything is about getting things done as quickly and efficiently as possible. If you stop you get cold. It’s dangerous. You have to focus on doing just what is necessary. I was grateful to have my experienced guide looking out for me. I certainly have a greater appreciation now of what these explorers and scientists did in these frozen regions. And I also know that a camping trip is not the best way to experience the northern lights.

* * *

This blog was first published on the International Year of Light UK website on 13th March 2015 as Notes from the North – Part 3. Read Part 4.

* * *

Plasma physicist and adventurer, Melanie Windridge, is on an expedition to the frozen wilderness of Svalbard to witness the northern lights. In a series of letters, she shares her experiences as she walks in the footsteps of the earliest polar explorers and battles the elements in pursuit of science. In her third post, we rejoin her journey as she continues to brave the cold and manages to see the northern lights.