Last Friday was an extraordinary day. Eclipse day. I awoke to mostly clear weather and couldn’t quite believe our luck. As I walked down through Longyearbyen towards the university (UNIS) just before seven o’clock, there was a large lenticular cloud hugging the summit of the mountain across the fjord, and some wispy, pink cirrus clouds up high. Otherwise the sky was blue. I met my friend Pål (pronounced Paul) at UNIS, an optics specialist in the atmospheric physics group, and we went across to the old aurora station in Adventdalen. Visiting scientists were there setting up their equipment for imaging and spectroscopy, and the Norwegian broadcaster NRK was preparing for a live broadcast. Pål set up his telescope and camera. The clouds disappeared and the sky became a perfect blue, the sun shining strong and clear and reflecting brightly around the snowy mountain landscape.

After nine a group of students arrived. Up and down Adventdalen people were gathering. It was freezing – probably around -20C – and I was wearing full down clothing. People walked around between small groups, trying to keep warm and anticipating “first contact”. Then, at about twelve minutes past ten local time, there it was. The moon touched the sun and we watched it gradually move across, people tracking the progress through their eclipse glasses. We also had a Sunspotter, a folded Keplerian telescope which projected an image of the sun onto a small screen. People gathered round to watch.

Gradually the sun shrunk down to a small crescent, then a sliver. At this point it became noticeably darker, though still quite light. “It’s just like looking through sunglasses,” I heard a student nearby exclaim. Except we weren’t wearing sunglasses. Then, a strange strobe-like effect began, clearly visible as flickering light-and-dark on the snow. These were the shadow bands – rippling waves of light caused as the final, almost point-source, sliver of light is focussed and defocussed as it passes through warmer and cooler air currents in the atmosphere. People talk about watching out for the shadow bands because they are easy to miss. Experts recommend putting a white sheet on the ground because they are most visible on a flat, white surface. There they were obvious – we had a landscape of pure white snow all around.

Incredibly quickly, after seemingly only a few pulses of the strobe, there was sudden brightening, the diamond ring effect, and then darkness. Totality. The moon was completely blocking the sun and I looked up at it with naked eye. I could see the pink tinge of the chromosphere (so called because of this distinctive pink colour) and prominences, though the fine structure of the prominences was more visible by telescope than by eye. I think I just saw the colour. The solar corona glowed silver, a ring around the dark shape of the moon stretching short, silky fingers outwards into the black. It looked fairly symmetrical to me, not highly pinched in any direction. It was like the sun had taken on the moon’s sheen, an eerie, ethereal silver. It was beautiful. I looked around at the mountains. The darkness was not pitch black, more a navy blue, perhaps from all the snow to reflect the light. The mountains could be seen clearly and the horizon all around gave out a yellow glow. People stood staring up in awe.

All too soon there was another bright burst of light and the sun was back. I fumbled in my mittens to open my eclipse glasses again and looked up to see the newly exposed crescent of the sun as the moon moved on its way. I took a deep breath as people around whooped and began discussing how incredible it was. I couldn’t quite believe that I had witnessed a total solar eclipse. I felt elated. It had all worked perfectly. I was in Svalbard, the weather cleared, the heavens aligned. To be in such a phenomenally beautiful setting in the wide valley, with the mountains around, the snow, the light – it was special.

After totality we watched the sun return to us in full, everyone talking excitedly about what they had seen. Then at twelve past midday the moon made last contact and was gone. Everyone packed up and left, leaving Adventdalen deserted once more. Apart from the scientists taking measurements from inside the old aurora station building, Pål and I were the least to leave, clearing the place up like at the end of a party.

A lecturer at UNIS last week compared a partial and total eclipse thus: “it’s like a kiss on the cheek versus a night of passion.” It’s true. I saw the partial eclipse near London in 1999 (I didn’t go to Cornwall) but I wasn’t prepared for the difference. What I found most interesting, most incredible, this time was the sudden transition from light to dark, from crescent to corona. It was the way the land went dark almost instantaneously that really struck me – one minute strobing shadows, then a bright flash, then darkness. Then the sun as you have never seen her. I have seen pictures of the corona before but, just like viewing the aurora, to witness it as part of the landscape gives and new depth to the experience, something that I am exploring in my upcoming book, Seeing the Light.

I am truly grateful to have been there in Svalbard to see the eclipse. I’m pleased that there was so much excitement and activity in the UK, and that so many people were able to get a glimpse of the splendour of this celestial event for themselves by viewing the partial eclipse. But I urge you to remember that if you saw the partial it was just a glimpse, and I hope that one day you will have the opportunity to see totality for yourself too.

* * *

This blog was first published on the International Year of Light UK website on 23th March 2015 as Notes from the North – Part 4

* * *

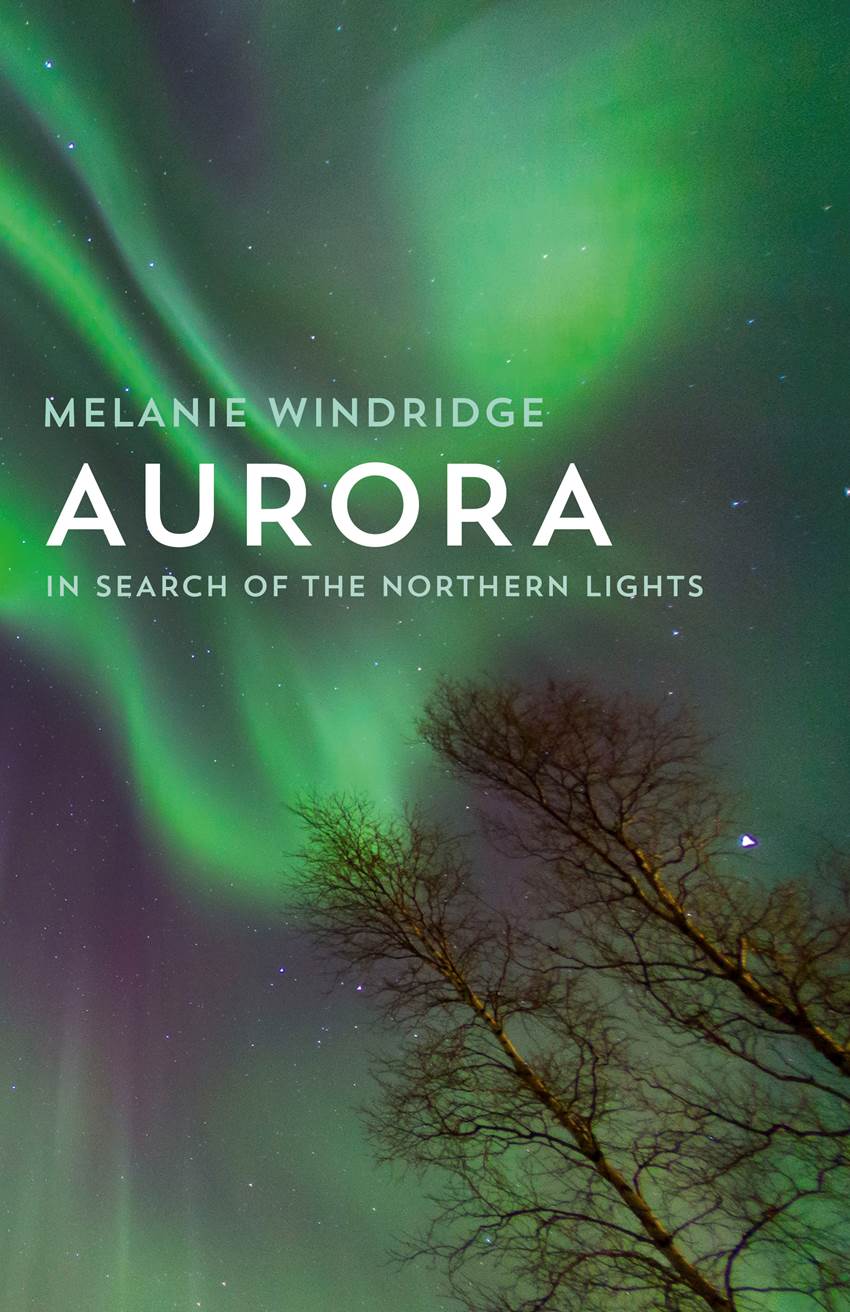

Plasma physicist and adventurer, Melanie Windridge, is on an expedition to the frozen wilderness of Svalbard to witness the northern lights. In a series of letters, she shares her experiences as she walks in the footsteps of the earliest polar explorers and battles the elements in pursuit of science. In her fourth post she has a front row seat to one of the biggest events of the International Year of Light – a total solar eclipse!