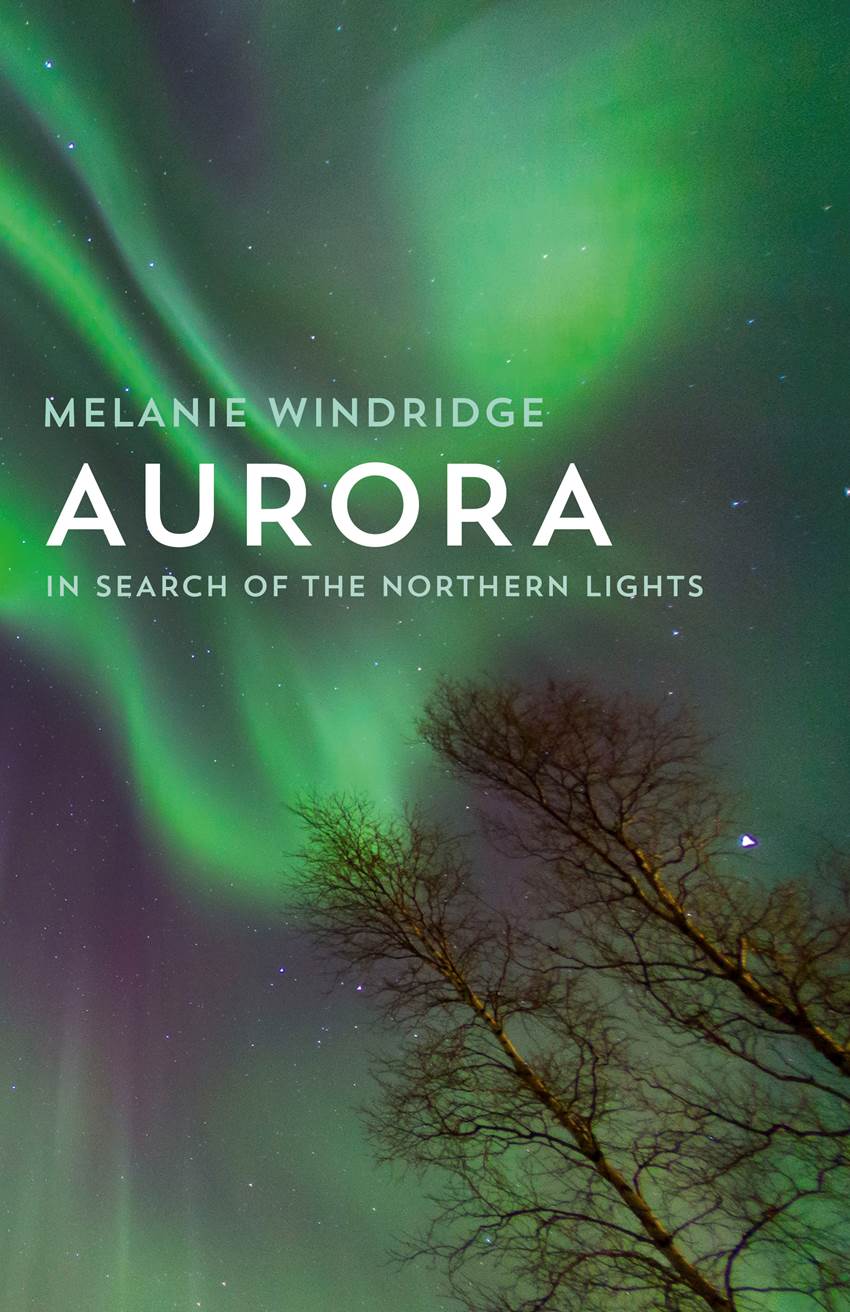

This post is in response to comments on my Facebook page in relation to the Nature article Women in physics face big hurdles – still.

Read the original post and comments. (Update – alas the commenter chose to delete his comments after I wrote this post.)

Image of my original post on Facebook. Click to read the comments.

To D,

Thank you for your comments about women in science. I hope you don’t mind me addressing them more fully than the Facebook comment section allows. Here are some of my thoughts on the subject in response to yours.

Firstly, I don’t think sexual harassment is the main issue in keeping women out of science, though I do think you underestimate the effect on young women. It’s not simply about fending off ordinary advances (which are a part of normal life); it is about young, early-career women feeling pressurised by older, influential colleagues and the fear that rejection or scandal could damage their career. It’s the awkwardness, worry, shame, self-doubt… none of these are good feelings in the workplace.

But, as I said, I don’t think harassment is the main reason for lower numbers of women in science. Harassment happens elsewhere too. I think the problem is more to do with girls feeling that they won’t fit in – the lack of role models, the entrenched stereotyping, the underestimating of their abilities. This is particularly strong in the physical sciences. The lack of women perpetuates a lack of women.

Yes, girls are making these choices to not go into science (particularly physical science) but that doesn’t mean it isn’t a problem. The future strength of the economy requires more people – of both genders – studying science and maths, so it is in everyone’s interest to take the reason for these choices seriously. Burying our heads in the sand helps no one.

Averil Macdonald, research lead and author of the People Like Me resources, says of this “choice” that young girls make, “how would we feel if it became clear that boys were implicitly being told in schools and by parents that they shouldn’t choose to enter law, for example, and thereby were being cut off from good salaries and prospects?” She makes the point that this might also risk skewing the way that the UK legal system worked, which wouldn’t be good for society. Why is it different for girls and science?

I believe we need to help girls to realise that science can be for people like them (not just “strong” women who defy the conventions). The beauty of physics is that it is so broad and so relevant to our lives, even if it sometimes seems quite abstract at school. Physics and maths are tools that can be applied in many areas encompassing varied interests: on the social side, like healthcare and energy; to the adventurous, like glaciology and volcanology; to the abstract, like finding the Higgs boson or dark matter; and in business of all kinds. With such a range of subjects there is clearly room for a variety of characters and skill-sets, so there is no reason for girls to feel that they wouldn’t fit in.

You ask why women aren’t rushing to solve the problem and study physics if more and more people are becoming passionate about these issues. The answer is that it requires social change and will likely take generations. We need to stop telling our children that some things are “for girls” and some things are “for boys”. We need to show them the relevance of physics and maths throughout their schooling, giving them a feeling for the range of applications and the variety and importance of science roles in all areas of society (even in the Arts there are roles that require science and maths skills). And we need to give our girls the confidence to feel that they can make a difference there too.

Yes, this is what we are still telling our children. Really.

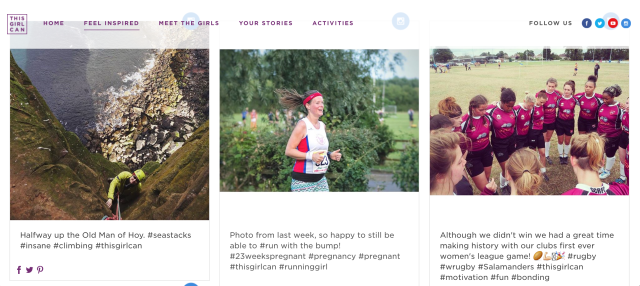

We should be telling girls that they can be and do anything they want – not pushing them down with slogans like “Too pretty to do maths”, above. I like the Sport England campaign This Girl Can, which inspires women to push their boundaries. The same sentiment can be applied to women in science. (Incidentally, I’m featured on their Inspiration page with my post from climbing the Old Man of Hoy.)

Let’s inspire our girls to push the boundaries of what they can do and not stifle them with stereotypes. #thisgirlcan

I am grateful to have such a rewarding, exciting, varied job in physics. I don’t think everyone should be a scientist. But I don’t want girls to miss out on interesting, fulfilling careers because of out-dated stereotypes.

To find out more about the work going on in this area and why, take a look at the following organisations (ones that I have been privileged to work with or alongside):

Your Life, The Ogden Trust, Institute of Physics, WISE, The Royal Society, British Science Association, Institution of Mechanical Engineers.

And do take a look at the WISE work on People Like Me.

Best wishes.

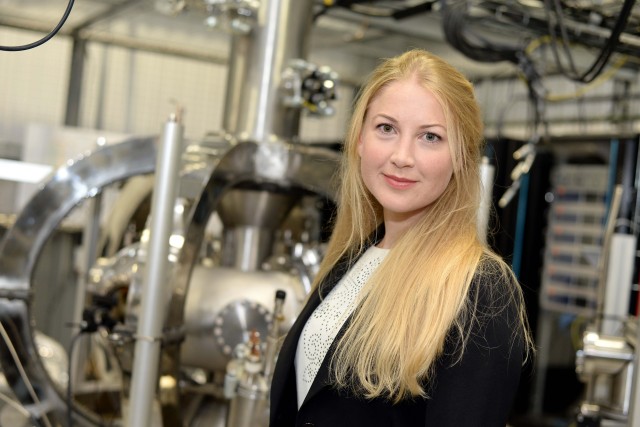

Me at Tokamak Energy, the fusion startup where I am Business Development Manager.

Featured image quote by Marianna Cheklin.