Craig Storti

Craig Storti is the author of the newly released book ‘The Hunt for Mount Everest’, which explores the history of the mountain before the 1920s and the first ascent. We spoke to Craig to find out more about him and his book.

1. Can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

My career has been as a trainer and consultant in the field of intercultural communications, about which I have written eight books. I grew up in New England (a proud Vermonter), went to high school in Wyoming, to college in Washington, DC, served two years in the Peace Corps in Morocco (as a teacher of English as a second language). When I was 14 I read a paperback called Annapurna (about the French expedition that climbed that mountain) and dreamed from that moment of one day seeing the Himalayas. I achieved my dream 18 years later in 1979 on my first trip to Nepal (where I met my future wife, who worked as a nurse in one of the health clinics Sir Edmund Hillary built for the Sherpas).

2. What sparked your interest in travelling?

I’d love to be able to say it was a quest for adventure, but actually it was more mundane: I wanted to stay alive. It was 1970, the Vietnam War was at its height, and I didn’t want to be drafted and sent to war, so I joined the Peace Corps which was an automatic draft deferment, and was sent to Morocco. Had I known, I like to think I’d have gone anyway, but that war was a real incentive.

3. Why did you decide to write your book, ‘The Hunt for Mount Everest’?

When I lived in Nepal, from 1980-1982, I read everything I could find about the Himalayas and Everest. I remember thinking then—40 years ago—that all the Everest books start in 1921 with the first-ever expedition, but someone should write a book that ends in 1921, Everest the Prequel. I didn’t expect to be the guy who did this, but then it did take me 40 years. When I started I wondered if there was enough material for such a book, but I need not have worried. This is actually my 10th book, but the first that has real mainstream appeal, and I am delighted with how it has turned out. From the beginning I wanted it to be a page-turner; readers will be the judge, of course, but my wife said she couldn’t put it down (at least not when I was looking).

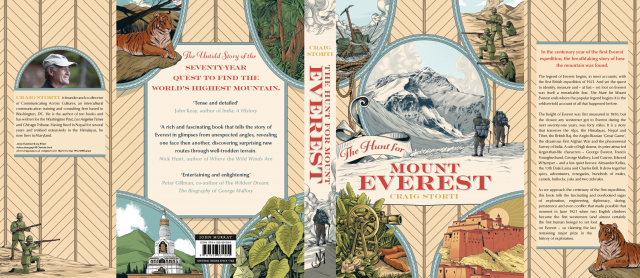

The Hunt for Mount Everest book cover

4. What was the most surprising discovery you made while writing the book?

This is not what you mean by this question, but my biggest surprise as I was writing was to realize that 2021 would be the 100th anniversary of the first expedition, the climax of the book. How cool was that? Now on to the question: I love the story of Alexander Kellas and everything about the man. This was not a surprise, as such, but a fortuitous discovery for a writer; among all the larger than life characters, this quiet man makes the book that much more gripping.

5. Why do you think it’s important to know the history of Mt Everest?

Gosh, I really don’t know if it’s important per se, but I think people will be interested just because the mountain is the most famous in the world. And while the climbing history is relatively well known, the back story is not. And it’s fascinating.

6. What’s your favourite part in the book? Could you share a little snippet with the readers?

Gosh, this is hard, but I’ll share two snippets, if I may. The first is the final paragraphs of chapter 3 about the invasion of Tibet, which sets the stage for British involvement with the country, hence with Everest. The second is about Kellas.

Book excerpts

1.

“In Tibet, all was quiet. After renegotiating the agreement with the Tibetans, Frank O’Connor, now the agent in Gyantse, was not especially busy. Indeed, apart from those negotiations, O’Connor is perhaps best remembered for buying a Baby Peugeot in India, having it disassembled and carted over the Himalayas, and then putting it all back together in Gyantse, where he offered short rides to delighted Tibetan friends and dignitaries. The Peugeot was always shadowed by a team of horses on these excursions due to the tendency of its carburettor to fail for lack of oxygen at such high altitude, whereupon the horses were hitched up to the Peugeot and it was dragged back to Gyantse.

From virtually any perspective – whether military, diplomatic, economic or political – the entire Tibetan affair, the last act of the Great Game, was just short of an embarrassment. For all it cost in terms of lives lost – close to 3,000 Tibetans, 4 British officers, 1 native officer and 28 sepoys – and financial outlays, almost nothing of any consequence was achieved. At the end of fourteen months of effort and several fierce battles and after the discovery of a grand total of three Russian-made rifles in Lhasa – they were ‘considerably scarcer than Huntley & Palmer biscuits’ – the British now had a trade mart and a commercial agent at Gyantse and another mart at Gartok. Business was not brisk. But then Tibet did at least have its first Baby Peugeot.

And thus the Great Game ended, not with a bang but with a whimper.

Unless one was a mountain climber, that is, especially one from Britain, for in that case the invasion of Tibet changed everything. For one thing, it marked the beginning of the end of Tibet’s isolation from the outside world, and for another the terms of the Anglo-Tibetan Convention gave the British a modest toehold in the country, just enough, it was believed, for the Tibetans in good time to be persuaded to permit the British to conduct exploration and mapmaking activities. And it was precisely this prospect that was so tantalising to climbers, for if Tibet could be explored, then sooner or later surely Mount Everest could be found.

He might be persona non grata to diplomats, bureaucrats and politicians, but Francis Younghusband would forever be a hero to mountaineers.”

2.

And another, about Kellas of course:

Alexander Kellas

“Alexander Kellas was chasing a record. While not an especially vain man, he was proud of his climbing achievements, and on this particular journey to the Himalayas in the summer of 1911, he knew he stood a chance of breaking Tom Longstaff’s record, set four years earlier on Trisul, for the highest summit ever climbed. At the moment, however, in his camp somewhere on the lower slopes of Pauhunri, he was more concerned about two young lark chicks whose parents had apparently abandoned them. ‘Quite unwittingly, we [had] erected our tents about three yards from a nest. From the plaintive notes heard after we had settled down, I was sure that we must be trespassing, and on looking found the nest with two young ones.’ Kellas worried that the parents were hesitant to come too close and had stopped feeding the chicks. ‘I was inclined to move the tents as I was afraid the [young ones] would starve.’

It is typical of the man that Kellas could be absorbed in the challenge of setting a climbing record and at the same time anxious about the suffering of two young larks. He was a man of many contradictions: he was a professor and an avid climber; a scientist who heard voices; a recluse who became famous; slight of stature and yet renowned for his physical stamina. Kellas’s duelling personas were a rare combination in the mountaineering fraternity, making him an unusually appealing figure, but they in no way handicapped or diminished him: he quickly became the most successful and also one of the most-beloved Himalayan climbers of his generation.

Kellas kept a vigil over the young larks for several hours and was greatly relieved when after some time ‘one of the [parent] birds came to feed them and continued to do so at intervals of a few minutes during the afternoon and next morning’. And what of the climbing record? Did he break it? He did manage to climb Pauhunri that summer, reaching the top on 14 June, but at 23,180 feet (7,065m) that mountain, alas, was 280 feet (85m) lower than Trisul. Or so everyone thought.”

Find out more about Craig and his work on his website. ‘The Hunt for Mount Everest’ can be purchased here.

For more stories, visit my other blogs here. Follow me on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram for more updates.