Mountain Science – preliminary results 2

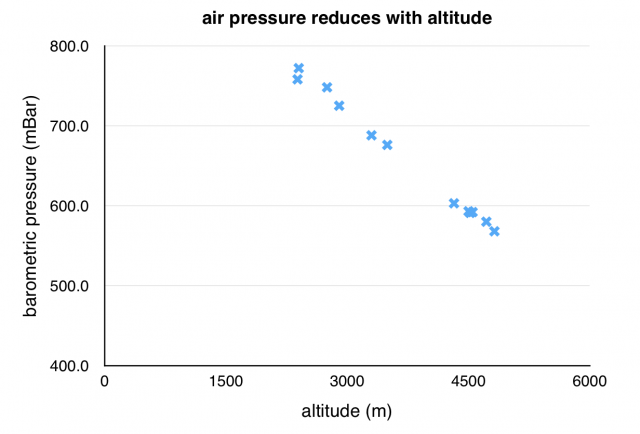

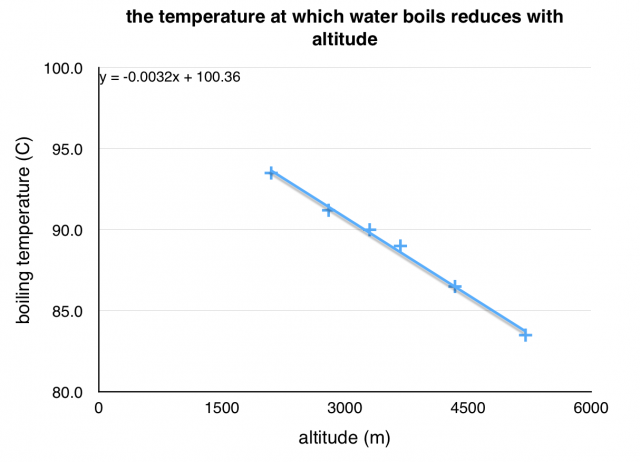

In the last blog we looked at how air pressure reduces at altitude and the effect this has on the boiling point of water. This reduced air pressure also has a serious effect on the human body.

Reduced air pressure means that there is less oxygen available to the body. There is still the same proportion of oxygen in the air (almost 21%) but the air pressure is lower so there are fewer air molecules per fixed volume of air. This means that for every lungful a climber breathes there will be fewer oxygen molecules going into the bloodstream.

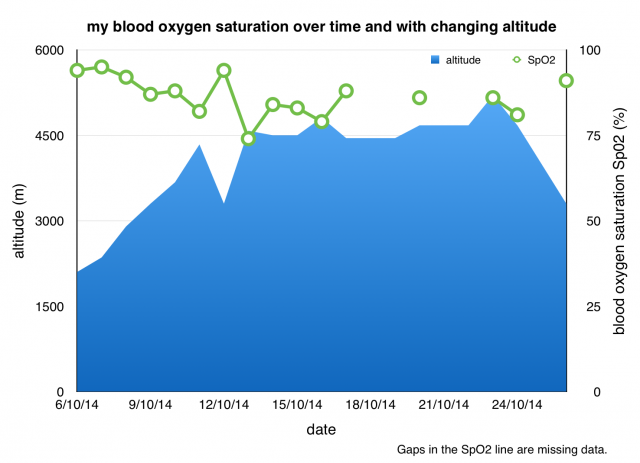

Doctors measure something called oxygen saturation (the concentration of oxygen in the blood). Below 90% is considered low, and at sea level people with oxygen saturation this low would probably be sent to intensive care. The interesting thing is that bodies can adapt to low oxygen environments and most climbers at altitude will have oxygen saturation levels below 90%, as I did for most of the time on my trip (see graph below).

Blood oxygen saturation, also called SpO2, can be measured using a little device that fits on our finger, called a pulse oximeter. This picture below is me measuring my SpO2 at home before I left for the mountains. You can see my SpO2 was 97% then. The 57 is my heart rate.

The graph below shows how my blood oxygen saturation varied during the climb. The blue “mountain” shows the altitude and the green points are my SpO2 measurements. They are not tremendously accurate, but they give a clear picture of how changes in altitude affect the oxygen in the blood.

In general, my SpO2 correlates quite nicely with the altitude. At the beginning of the trip as we ascend the oxygen saturation in my blood goes down. When the altitude drops my SpO2 goes up (e.g. around 12/10/12) and then drops again as we ascend further.

Unfortunately there are some data missing from the second half of the trip so we don’t get to see if my SpO2 increased as I acclimatised during the spells at a fixed altitude. However, acclimatisation aside, it is clear that the reduction in air pressure at altitude has implications for our body. The oxygen saturation in our blood – the oxygen available to our cells to keep the body alive – reduces as we go higher.

It is really important to be aware of this effect because oxygen is essential for our survival. Every year people die of altitude sickness in the mountains when their bodies don’t get enough oxygen. This can cause fluid on the lungs and on the brain, which can be fatal. Mild symptoms are headache, nausea and fatigue. Most people will experience mild symptoms, but if they are very bad or if you experience breathlessness at rest or confusion, clumsiness or stumbling you should go down immediately.

For more info on air pressure and oxygen levels, and for advice on climbing and altitude sickness, see altitude.org. Also have a look at the Centre for Altitude Space and Extreme Environment Medicine (CASE Medicine) where they study the medicine and physiology of extreme environments.

Alongside Anturus I am making some videos of these experiments as educational resources, but these are some first results.

Thanks to my sponsors: