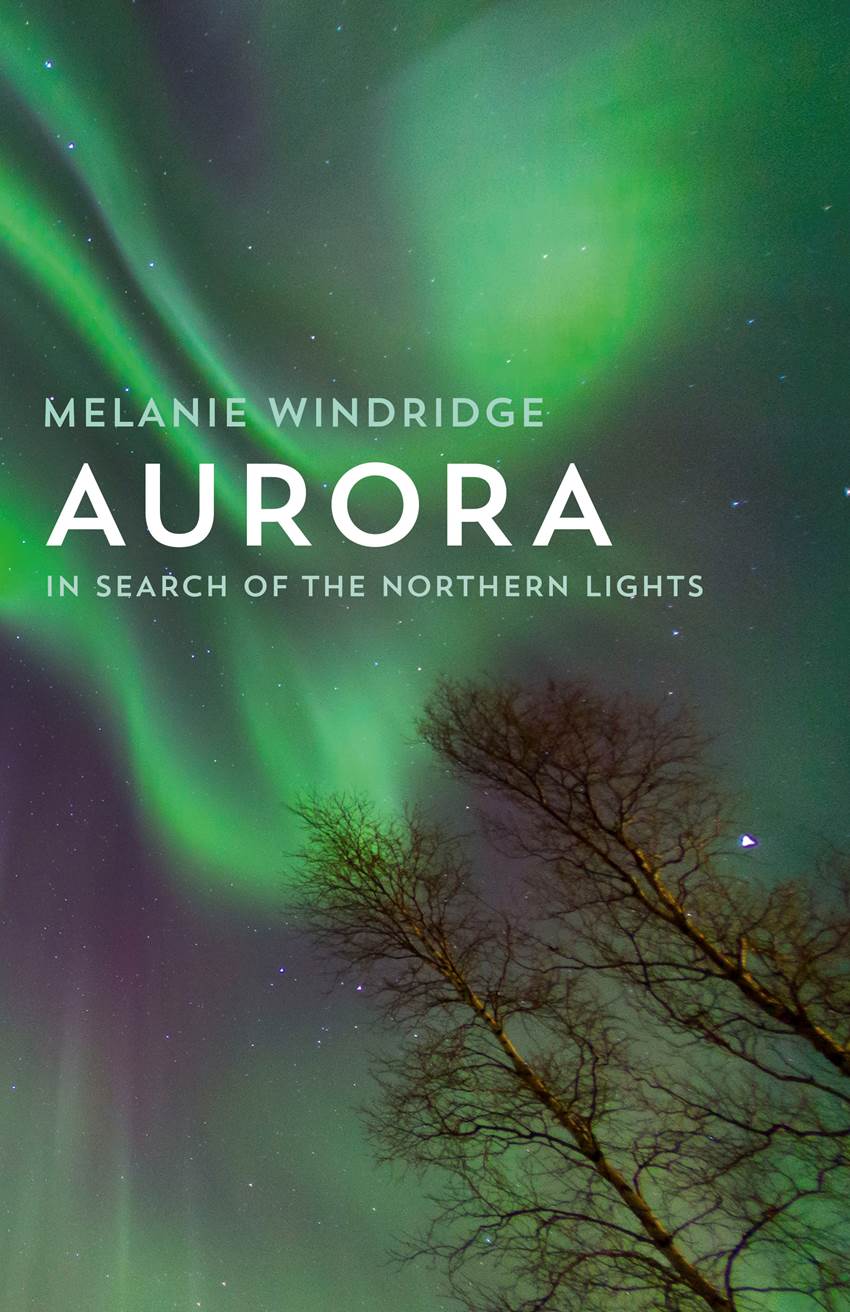

Aurora: In Search of the Northern Lights came out in the USA this week, so here is an extract from the book about auroral substorms – the aurora pattern that was first noticed by a researcher from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

Aurora appears over the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Courtesy of Taro Nakai.

Being up in Yellowknife with James Pugsley and discussing the nightly patterns of the aurora highlighted how little I actually knew about the northern lights. I am a scientist and I have an under-standing of the physical processes that cause the aurora, but I’ve only seen it a few times in my life. I can’t really say that I know the aurora. That is why people like James, who live in Yellowknife and who have profound experience, can be so valuable to a project. They bring different perspectives and expertise to the discussion. The success of a project like AuroraMAX is partly due to the mix of people involved: a basis of strong, knowledgeable scientists like Eric Donovan at the University of Calgary, run by the dynamic and dedicated James and with support from the Canadian Space Agency.

James has seen so many auroral displays that he knows what to expect each time and this helps him to set up his cameras in the right places to get the best photographs. The regular flow of the Dungey Cycle creates reproducible patterns in the aurora that are recognisable to the trained eye. It may be a turbulent process producing unique displays but the substorm process shows definite commonalities in form. Scientists like Eric in Calgary have studied countless images to track the evolution of the aurora night after night. ‘It’s a consistent response of a complicated system,’ said Eric. ‘In some way substorms always look the same. It’s like an explosion but they all look the same.’

Substorms have three main phases – the growth, the expansion and the recovery. The substorm pattern was first noticed by a young Japanese researcher, Syun-Ichi Akasofu, from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, in 1964. He had been studying all-sky camera images made during the International Geophysical Year of 1957–58, which was scheduled over a solar maximum. This was another year of intensive worldwide scientific collaboration. This time a network of all-sky cameras had been set up across the globe, in both the Arctic and the Antarctic. Including observations contributed by amateur enthusiasts, the images gave the most complete picture of auroral activity thus far. Akasofu noticed that occasional but intermittent times of brightness and activity interrupt the other-wise quiet auroral oval. This activity happens furthest away from the Sun, so at midnight. The Earth is constantly turning under this oval, which remains fixed around the magnetic pole, and so a particular point on Earth will experience different auroral conditions as it moves relative to the Sun, moving in and out of the auroral oval as it goes.

Diagram showing how Scandinavia and Svalbard move in and out of the auroral oval as the Earth rotates, and how the auroral activity varies around the oval relative to the Sun. The Sun is out at the top of the page, so midday is correspond-ingly at the top of the diagram (closest to the Sun) and midnight at the bottom. Courtesy of Robert H. Eather. Egeland & Stoffregen, Norwegian Academy of Sciences and Letters.

I talked with James about his experience of substorms and asked him what he normally sees in Yellowknife.

‘“Normal” to us means that we are seeing some nice bright green aurora,’ he said. Even when the solar wind and magneto-spheric conditions are quite calm and normal, Yellowknife will still have a beautiful, predominantly green, aurora and there will be some sort of break-up. The structures are always similar and they occur directly above. The arc of green light starts in the north, works its way overhead to the south, releases energy in a bright-ening and breaking-up of the arc, then comes back to the north. The oval expands and then it contracts. If the event is relatively substantial, alongside green tones James may see some of the pinks of nitrogen as the incoming particles penetrate down to 80–90 kilometres (50–60 miles) above the surface of the Earth, where they create some of the more vibrant colours.

Almost every single night they see a similar process occur as the system goes through the same, repeatable phases. It may not be very intense; it may be very gentle. Some nights the auroral arc stays directly overhead, rather than pushing all the way south, and there’s no big break-up – just a soft release before the arc transitions back to north. As James said, ‘It’s as if the wash, rinse, repeat is still happening but it’s happening in a very subtle way.’

This video shows the substorm process playing out over a whole night of auroral activity.