“You should be here earlier in the winter. When it was colder,” said Knut, the Sami reindeer herder in his gruff, accented English. “Now it’s warm weather, rain, we can’t see the northern lights.”

“We haven’t seen them at all since I’ve been here,” I replied. “That’s nearly a week. It’s been cloudy every day.”

“When it’s so warm it [the northern lights] doesn’t come.”

“When is the best time to see it?”

“December or January. When it’s very cold.”

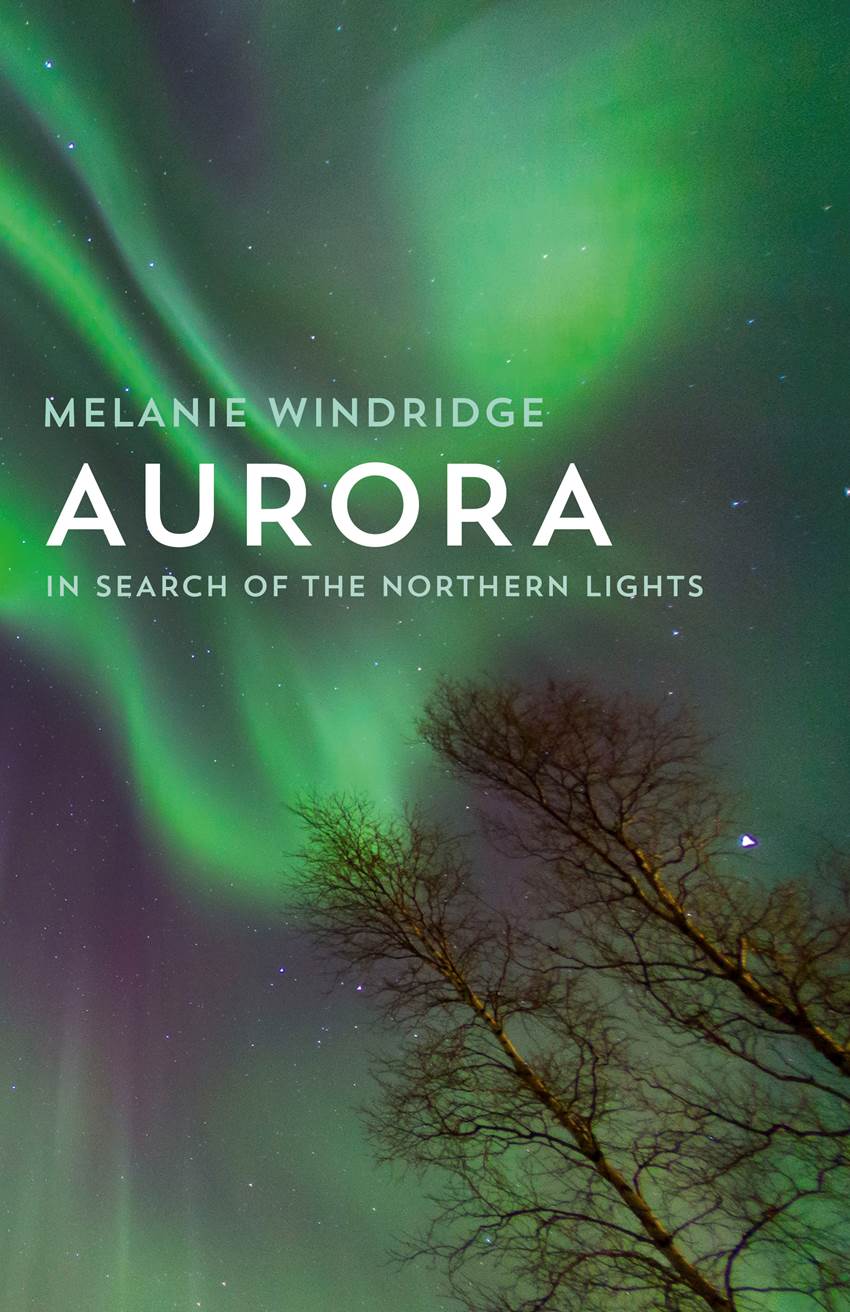

We were out in the hills with the reindeer somewhere around Karasjok, a few hours’ drive inland from Alta, near the Norwegian–Finnish border. That was March last year. I was in northern Norway researching a book I am writing on the northern lights. I am a plasma physicist and the aurora is plasma, so despite my academic interests in nuclear fusion (I was the IOP Schools’ Lecturer in 2010 on this subject), the northern lights have long fascinated me.

In Norway I was finding out about Sami culture and their folklore. “My parents told me that it was the spirits of the dead peoples, our relatives,” said Knut. “They were watching us.”

Since that trip I have visited Canada, America and Iceland – speaking to physicists, visiting tiny observatories, learning about space weather, geology and geomagnetism. And it all culminates this year – 2015, the International Year of Light. I’m going to Svalbard, the Norwegian archipelago in the high Arctic and the most northerly place in the world with a permanent population (though the people are outnumbered by polar bears). I’m going to see two of the most spectacular phenomena involving light on Earth – the northern lights and a total solar eclipse. Let’s just hope it’s not cloudy.

For me, the chance to see both these phenomena together is a lucky coincidence. Solar eclipses happen around once every year or two somewhere around the globe. A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between the Sun and the Earth, thereby blocking the light of the Sun. Although the Moon passes between the Earth and the Sun once during each monthly cycle – the new moon – most times they don’t line up exactly. The Moon’s orbit around the Earth is tilted with respect to the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, so the shadow of the Moon often misses the Earth. Thus eclipses happen infrequently.

This total eclipse (which occurs on 20 March) happens to coincide beautifully with the research for my aurora book, when I will be in Svalbard chasing the lights in an unconventional way. The first two weeks I will spend skiing east–west across the largest island of the archipelago, Spitsbergen, dragging my equipment and food in a pulk behind me, camping out in the snow, hoping to witness a good auroral display out in the Arctic wilderness. I will be with a guide, and we will be looking out for polar bears.

It will be more difficult than usual because it will be mostly dark. When I arrive on 16 February, the island will just be emerging from polar night, the sun rising for the first time since October last year. But the sun comes back quickly and by the end of my ski journey 10 days later there will be about seven hours of daylight. If I’m lucky I might catch a glimpse of the dayside aurora, only visible during polar night, for which Svalbard is particularly known.

Svalbard hosts some major research facilities including the European Incoherent Scatter Scientific Association radar, the aurora station at the Kjell Henriksen Observatory and a satellite station. It’s a good place to study the northern lights because the island’s high latitude position gives it an interesting perspective. The Earth’s dipolar magnetic field is not aligned exactly with the axis of the Earth (and indeed the geomagnetic field varies and wanders), meaning that the magnetic poles are not aligned exactly with the geographic poles. The dipole is tilted towards Canada.

Svalbard is located underneath the northern polar cusp, where the Earth’s magnetic field opens out into space like a funnel and charged particles directly from the Sun can enter and reach the Earth’s atmosphere. Here they excite atoms in the air, which then release this extra energy as light of characteristic colour. This direct funnelling from the Sun side of the Earth results in daytime aurora, which is less bright than night aurora and usually red in colour, since the incoming particles have lower energy. But how, you might be wondering, do charged particles get round to the night side of the Earth and create the northern lights there? And how are they accelerated to the higher energies required for those more vivid, colourful displays? That is the magic and mystery of the true aurora, something I will be exploring in my book.

As for the solar eclipse, I don’t know what to expect. But I do know that the town will get very busy with visitors from all over the world. Solar eclipses are not just beautiful, they offer a short window to make important scientific measurements. Einstein’s theory of general relativity was confirmed using observations made by Sir Arthur Eddington during the 1919 total eclipse.

Hopefully the weather will be kind and I will glimpse the solar corona and the complex, ever-changing magnetic field pattern, imagining the solar wind particles travelling to Earth and causing the aurora. I will be thinking about how it affects us on the technological, disruptable level we call space weather and also about how studying light has enabled us to increase our understanding of the universe.

Yet phenomena such as these also touch us on a personal, spiritual level. It interests me that even now, while understanding the physics, we still feel the wonder – even the spirituality – of these natural events. Standing captivated under a wide sky, watching the heavens move in a graceful, barely-choreographed dance, it’s easy to see the inspiration behind those old Sami tales.

* * *

This blog was first published by the Institute of Physics on 4th February 2015 at http://www.iopblog.org/melanie-windridge-northern-lights/

* * *

Hi Dr.

Thanks for the article, interesting read. I’m planning to travel there in mid December 2015 for a week, and hoping to get a good display.

Best,

S.

Good luck! Make sure you get out of the city lights.